The Emplawas people live in the Babar Islands in the South West Pacific near North Australia. The Babar Islands are thought to have been inhabited for 40,000 years, starting with Australoid people then more recently (from 3000 years ago) with waves of Austonesians mixing in. The Babar Islanders were traditional animists and pretty much left alone until about 100 years ago when the Dutch colonial government forced them all to come down out of their cliff-top fortresses and live by the beach and stop warring with each other. Church officers from the Maluku Protestant Church (/Gereja Protestan Maluku-GPM)/ were dispatched to "civilize" and christianize the Babar Islanders /en masse/, build church structures and install priests to conduct religious services. The GPM, the dominant religious institution in the Babar Islands, is 403 years old (founded in 1605); Asia's oldest Protestant denomination. The communities of the Babar Islands are nominally Christian, but there is little evidence of faith. The spiritual lives of Babar Islanders are a mixture of Christianized surface symbols and rituals layered over their deeper traditional animistic and occultic practices.

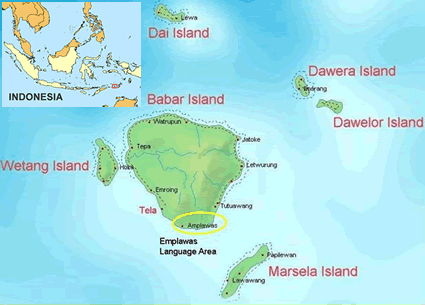

The Babar Islands are located roughly 160 miles east of East Timor and 300 miles north of Darwin, Australia or 7 degrees 66 minutes south and 129 degrees 40 minutes east. The arid Australian climate has a significant effect on the Babar islands. While there is plentiful rain from Christmas till June, there is no rain from July till Christmas again. The wind blows almost constantly from the East from April through December, and from the West from January to March. There is a calm season in both November and March.

Babar Island, the archipelago's namesake, at a height of around 700 meters dominates the local horizon. While Babar Island itself is relatively fertile and has abundant water due to its size and height which attracts rain clouds, it is surrounded by five much smaller and lower islands (located roughly at the cardinal directions) that are arid and infertile.

Most villages are located at the seashore either on flat sandy areas or amongst house sized coral boulders, cliffs and outcroppings. Every village has coconut palm trees towering above the thatch rooves providing shade and a constant whispering in the never-ending trade winds. Most houses do not have glass windows and are open to any breezes that might chance by, allowing flies, mosquitoes and dust ample opportunity for entrance.

Everyone lives in villages within a few metres of the ocean. Most people rise before dawn with the crowing roosters and the twitter of tiny birds and amble down to the ocean to relieve themselves. Alternatively they walk to the back of the village near the invariable cliffs to do their business, contributing to the risk of cholera spread by the abundant flies. Also at dawn from every household comes the rhythmic swishing of some adult female invariably sweeping the dirt yard with a long whisk. A deep thumping that shakes the earth from various quarters signifying some woman using large mortars and pestles to pulverize maize (a kind of white, starchy tasteless corn), their chief staple. They they grind the maize into a coarse meal, boil and eat it like rice.

Dogs, chickens, pigs and goats all prowl about the sandy streets and yards looking for morsels to eat. Partially or entirely unclad toddlers wander around in unsupervised gangs terrorizing grasshoppers. There are always women at home who start a wood fire in their kitchen hut and boil up some rice or pulverized maize for the day. The smoke of the cook fires seeping through all the thatch rooves rises to form a temporary haze in the still season. Many ladies fry donuts fresh or prepare their day-olds for sale to the kids on their way to school.

Mothers, aunts or older sisters serve up some cold rice or ground corn or a donut to the school aged children after they have washed their faces and put on their red and white school uniforms. At 7 am a teacher in a tan uniform at the school rings the hand bell and the children line up at attention and then all march into school. Some girls will carry a large Tupperware bucket full of donuts for sale at school.

Many of the men have already "saddled" (with a pile of burlap sacks) up their tiny emaciated horses and headed off into the forest to chop down trees for a new garden, move their cattle they have tethered in the bush, or to hunt wild boar, repair a storage shed, get building materials (rope from jungle vines, or palm leaves for thatch rooves, or giant bamboo), or do some weeding in their tangled gardens of corn/squash/beans. Others of the menfolk have paddled out a few kilometers to sea in their small dugout canoes to go fishing for small tuna with a line and hook, no rod. Some of the women bundle up their dirty clothes and detergent and head off on bicycle or foot to the stream a few kilometers away to pound their wash on the ancient, worn rocks. Some villages have no nearby stream so the women wash the clothes at the concrete public laundry plazas strategically placed throughout the village. At each plaza one faucet serves all comers.

At 8 am adult men and women in uniforms of brown, green, tan, grey or blue stroll along the streets on their way to their respective government offices, the men invariably puffing on a cigarette. In the remote villages the only kinds of government work are the different kinds of schools, the three or four village staff and possibly a health clinic. In the municipal capitols there are various kinds of church officials, policemen, military, postal, environmental, agricultural, education and many other kinds of civil servants.

By 11 am the youngest children are already headed home from school. Oftentimes they go play in the ocean, especially liking to play with dugout canoes which they use as surf boards. Once a week a couple children from each family are sent out to find firewood, which consists of dead branches as thin as their wrists. Hanging by a woven fibre strap that goes across their forehead, a pail-sized woven basket rides on their back ready to carry the firewood.

The men have come back from fishing and two kids in single file carry a pole horizontally between their shoulders with a few large tuna-like fish swinging by string from the centre and the boys call out "Ikan! Ikan" as they look for buyers.

Around 10 am you might see old men from every quarter shuffling their way to one particular house. If you passed by that house you would see them sitting around discussing in the indigenous language cases and lawsuits. One younger man stands by holding a bottle of coconut whiskey and a glass to take a drink to each elder who makes a short speech before quaffing back about an ounce's worth.

Around 1 o'clock the civil servants amble home from work unless they are a teacher. If you pass by some teacher's house in miafternoon you might see a group of 3 or 4 students getting a paid, private tutorial.

On many mornings can be heard the chug-chug-chug of a diesel engine of a small wooden boat arriving or leaving, ferrying goods and passengers from the municipal capitol to villages on other islands or villages that have no road. The boat weighs anchor 100 meters from shore beyond the pounding surf and dugout canoes weave their way out through the breakers to unload cement bags, boards, boxes of ceramic floor tile or corrugated metal roofing panels, along with passengers. People take live chickens, pigs and goats and garden produce or fruit if it is in season. Kitchen wares, plastic lawn chairs and stereo equipment might be seen unloaded. Coconut meat or bags of dried fish may be loaded to go to town for sale.

On any given day people will walk or bicycle or horse-ride to other villages on their island to shop, go to a government office or visit relatives such as childern boarding in town going to high school.

By mid afternoon most of the children are out playing. Swimming, marbles, dolls, complicated games that look like a combination of tag, British bulldog, and ten other games rolled into one, hopscotch, skipping rope, hunting and trapping birds or going with dad or mom to the gardens in the forest to do some "work" in the garden or to the clothes washing spot at the creek.

At 5pm there is often some kind of religious service so just before sunset you can usually see men, women or children freshly bathed and wearing their best clothes with their hair combed carrying an Indonesian Bible and prayer book strolling off to some kind of meeting.

The sun slips into the sea and about 30 minutes later outdoor electric lights all over town flick silently and simultaneously to life as the town's power comes on. All the children hoot and holler in celebration of a bright evening ahead of them with televisions and stereos mumbling or blaring throughout the village and a dim lightbulb by which to do their homework.

The Emplawas people believe first of all that there is a profound connection between all things physical and spiritual. Something done in the physical always has an impact on the spiritual. The other fundamental assumption is solidarity. They must remain united in their activities at all costs. Spending time alone is seen as a sympton of imbalance if not derangement. Doing things individualistically could also have negative spiritual and physical consequences. They think it is very important to be together at the various religious services and rites prescribed by the nominal church. While they do not understand the meaning of the rites they perfunctorily perform, they always complain about those who are absent, believing that the lack of solidarity will have a bad consequence like crop failure, injuries or epidemics. They believe that there are malevolent spirits all around them just waiting to pounce at the slightest provocation. So they have many folk beliefs for every aspect of life, designed to appease the spirits. They are afraid to go into the forest alone at any time, and especially not at night at which time they believe that blood-thirsty spirits wander about seeking whom they may devour.

The Emplawas people feel it is impossible for them to develop a decent standard of living. They are a minority in various ways (visibly, linguistically, culturally, religiously, geo-politically, historically) and they feel they are not allowed to advance and develop as they would like. There are resources and potential at their disposal which they could develop, however. Beyond the need for self-directed development of their islands, what the Emplawas people need most is the comforting, empowering and life-changing presence of the Holy Spirit received as pure gift by faith alone in the life, death and resurrection of Jesus. While the Bible in Indonesian is available, they neither understand Indonesian well enough nor feel enough positive attachment to it.

Pray for a spiritual awakening.

Pray that the Emplawas people be truly reconciled to God and indwelt by Him by faith and grace alone.

Pray for a Holy Spirit directed prayer movement for daily prayer for revival.

Pray for Emplawas evangelists to rise in the power of the Spirit to preach repentance and reconciliation to God.

Pray specifically against the stronghold of religious pride so the Emplawas people will listen to the pure message of reconciliation to God and abundant life by the power of the indwelling spirit by grace alone.

Pray for prophets, apostles and evangelists (Eph.4:11) to be filled with the Holy Spirit and rise up and confront and cast out demons, cast down and take into captivity every thought and principality opposed to God.

Pray for miraculous healings and other signs and wonders that confirm the truth of God's message of reconciliation to Him and abundant life in His loving presence.

Pray for the exposure of the works of darkness and the deceiving spirits that keep people in bondage.

Pray for godly sorrow and true repentance for sensual, escapist, selfish and cruel behavour; specifically unfaithfulness, promiscuity, unwanted pregnancies and herbally induced abortions, drunkenness, brawling, domestic violence.

Scripture Prayers for the Emplawas in Indonesia.

| Profile Source: Anonymous |